As Congress flirts with Medicaid cuts and Colorado’s budget crisis worsens, Western Slope health care providers brace for impact

When Congress ended automatic re-enrollment for Medicaid in spring 2023, a rural health center on Colorado’s Western Slope had no choice but to lay off staff.

Mountain Family, a federally qualified health center based in Eagle, Pitkin and Garfield counties, also froze salary increases and shuttered two school-based clinics to absorb the roughly $1.5 million hit to its budget.

Soon, clinics across Colorado’s High Country could face more of the same.

House Republicans in Congress last month took the first step toward approving a federal budget that is all but certain to include deep cuts to Medicaid, the government-subsidized health care program used by 1 in 5 Americans. At the same time, Colorado lawmakers are poised to pare back state Medicaid spending as they try to dig out of a growing budget hole now estimated to be $1.2 billion.

It’s left rural providers bracing for what comes next.

“Medicaid is a vitally important coverage source for our patients who are eligible and for our reimbursements from the state,” said Mountain Family CEO Dustin Moyer. “The impact of further Medicaid cuts would result in more hard decisions. I’m certain of that.”

In Colorado, an estimated 1.3 million adults and children — nearly a quarter of the state’s population — are enrolled in Medicaid.

Cuts at the state and federal level would affect coverage for “people with disabilities, older adults, people living in nursing facilities, children — who make up a substantial portion of the Medicaid population,” said Adam Fox, deputy director of the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative.

It would also have an outsized impact on the Western Slope, which already has a disproportionate number of residents who go without health insurance compared to the rest of the state, according to the Colorado Health Institute.

“It’s hard to, I think, fully quantify how devastating these cuts would be just because of the massive ripple effects they would have in rural communities,” Fox said. “You’d have thousands of people losing coverage. You’d have health care providers who can’t keep their doors open. You’d have local economies that suffer substantially.”

Compounding cuts

The end of automatic Medicaid renewal led to more than 575,000 Coloradans losing insurance and increased financial pressures on providers. What comes next from Congress could have an even greater impact on the program that provides health care to low-income Americans and people with disabilities.

A budget resolution approved by U.S. House Republicans directs the committee that oversees Medicaid to identify at least $880 billion in cuts over the next 10 years. That would be impossible without a steep reduction in Medicaid funding, according to a March 5 analysis by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

Lawmakers have floated ideas like capping federal Medicaid funding for states, instituting work requirements, and significantly scaling back funding for Medicaid expansion populations covered under the 2010 Affordable Care Act.

A spokesperson for Rep. Jeff Hurd, a Republican representing Colorado’s 3rd Congressional District, said the congressman does not support cuts to service but that there are ways to “eliminate fraud within Medicaid that does not impact coverage.”

Hurd, whose district spans much of the Western Slope, joined Colorado’s three other Republican representatives in Congress in voting for the House budget resolution, which Democrats all opposed.

Meanwhile, Colorado lawmakers have said an unexpected explosion in Medicaid costs — fueled by more patients using long-term care — has helped drive the state into a deficit. Since the federal government shares the cost of Medicaid with states, any cuts to the program would compound the reductions Colorado may already have to make as it seeks to balance its budget.

An analysis by the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation found, for example, that if Congress ended its 90% match rate for states with expanded Medicaid populations, it would cost Colorado $13.1 billion in federal funding over the next decade.

“We’re going to be looking at every possibility for how we trim back on Medicaid expenses,” said Colorado House Speaker Julie McCluskie, a Dillon Democrat. “But we cannot, as a state, absorb a $13 billion impact. It terrifies me.”

Hits to rural services

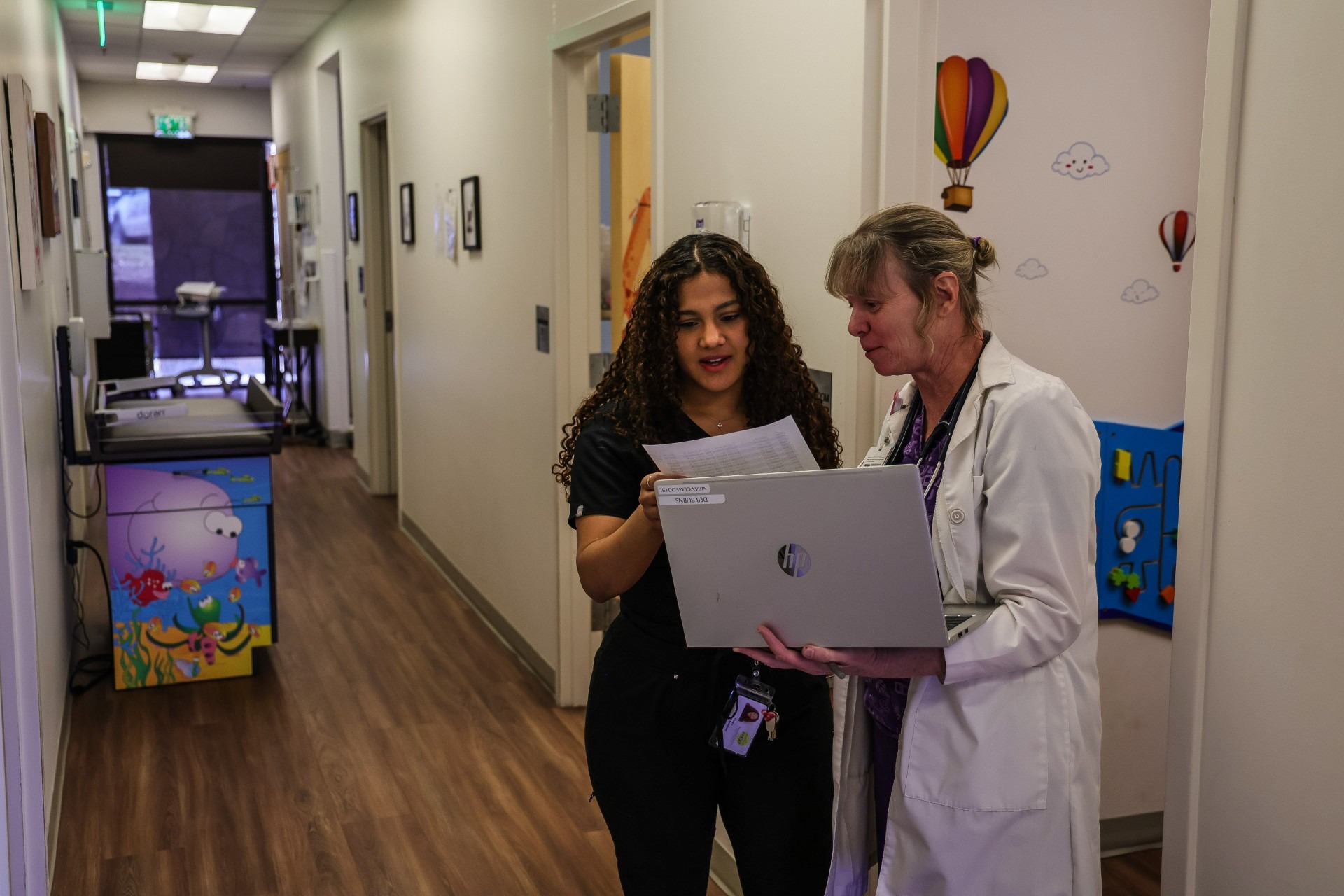

For tens of thousands of low-income Western Slope residents, a handful of federally qualified health centers, like Mountain Family, are their lifeline.

The centers, which rely heavily on Medicaid and other federal funds, are based in regions where access to health care is limited and offer services on a sliding pay scale. These clinics are also obligated to provide care to anyone who needs it, even if they don’t have health insurance.

Mountain Family sees about 20,000 patients and provides a slew of services like medical, behavioral and dental care. When Congress ended automatic Medicaid re-enrollment, around 2,000 Mountain Family patients were kicked off the program.

It meant the clinic experienced a double whammy of still having to service those patients without reimbursements from Medicaid, which makes up roughly 30% of its budget.

“I think community health centers are kind of accustomed to navigating a world where there’s thin margins,” Moyer said. “But it’s not just pressure on Mountain Family — certainly there is a lot — but it’s also pressure on our patients, on our hospital partners, really the entire community when we have to reduce our scope of services.”

State and federal cuts could amplify the problem, forcing health centers to scale back staff and services in communities already struggling with access to care.

Stephanie Einfeld, CEO of Northwest Colorado Health, a federally qualified health center based in Routt and Moffat counties, said its clinics are the only care option for some residents.

The center serves around a third of the region’s population, offering primary, behavioral and dental care in addition to in-home care, hospice, assisted and senior living and school-based services.

“We are the trusted resource for so many marginalized populations. We are the trusted resource for people who are low-income,” Einfeld said. “For a lot of the services we provide, we’re the only ones who will accept Medicaid and (the) uninsured.”

The health center is also a major employer in the region, supporting around 300 jobs. With Medicaid being one of its primary funding sources, the prospect of cuts “basically means that our entire agency is at risk,” Einfeld said.

In rural areas that struggle with acute issues of mental health, housing costs and workforce challenges, access to affordable or, in some cases, no-cost health care is essential to a community’s wellbeing, Einfeld said.

“Cuts to our funding just means that we don’t have the ability to combat those (issues) at the same level,” Einfeld said. “We don’t have the ability to keep our access as open as we would like. We don’t have the ability to serve all payer sources or people without insurance.”

The Summit Community Care Clinic, a federally qualified health center in Summit, Lake and Park counties, would do everything it could to preserve core services under Medicaid cuts, said Chief Medical Officer Kathleen Cowie.

While the clinic maintains around 50 local, state and federal grants, Medicaid still makes up about 25% to 30% of the funding for some services, while for others, it accounts for much more. Pediatric care is 90% covered by Medicaid.

Cuts to Medicaid “means that we have to limit our services, it means that we have to lay off staff, if it were a large enough kind of impact,” Cowie said

“We don’t want to close our doors to people when they don’t have insurance, but we also have to keep our lights on and pay our employees,” Cowie said. “And that starts to get really difficult.”

A cascading effect

Medicaid cuts wouldn’t just be isolated to community clinics and low-income patients. Local leaders say it would have a cascading effect on hospitals and insurance companies that would be forced to raise rates as a key funding source dries up.

“The health care system in America and Colorado is just extraordinary and deeply intertwined,” said Rich Cimino, executive director for Peak Health Alliance, a nonprofit that negotiates lower insurance rates in the High Country. “If hospitals and doctors are making less money from Medicaid, then they’re likely to increase the rates they charge for commercial insurance.”

Launched in Summit County in 2019, Peak Health sought to reduce health care costs for mountain town residents who were paying some of the highest premiums in the country.

By negotiating with hospitals and insurance carriers, the nonprofit can design lower-cost plans for specific communities. It claims to have offered its first plans in 2020 at rates 38% below those previously available.

Currently, Peak Health partners with Denver Health Medical Plans to offer insurance options in nine Western Slope counties, including Summit and Grand. Along with looming Medicaid cuts, Cimino worries other health care policy changes at the federal level could threaten those efforts.

Increased subsidies for the Affordable Care Act marketplace passed under the Biden administration are set to expire at the end of this year. The measure helped lower premiums and led to a record-breaking number of Americans who enrolled for coverage.

Republicans, who control Congress, are not expected to renew the subsidies as they look to fund an extension of tax cuts implemented under President Donald Trump’s first administration.

Cimino said some recipients could see their insurance premiums double as a result, forcing them to look for other options. He worries higher insurance prices could inevitably trickle down to the plans Peak Health negotiates.

Despite the progress that’s been made, Western Slope counties continue to see the highest health care costs in the state.

“If a whole bunch of people stop buying health insurance … well now not only are hospitals going to raise their rates because Medicaid doesn’t pay as much, health insurance companies are going to see their membership drop a lot,” Cimino said. “And so the price is going up just because there’s less people who have health insurance.”

‘A risk that’s always out there’

For rural health care providers, the fight over Medicaid is emblematic of the ongoing funding struggles that are their daily reality.

More than 70% of the state’s hospitals operate on unsustainable margins, while the cost of labor and supplies has risen by more than 30% since 2019, according to the Colorado Hospital Association.

Vail Health, a health care provider based in Eagle and Summit counties, has run on negative operating margins for the past three years, said Chief Strategy Officer Nico Brown.

But that hasn’t deterred it from pursuing an ambitious agenda.

The organization — which currently runs a 56-bed hospital, 24/7 emergency care services and several urgent care clinics — is on track to open a 50,000-square-foot inpatient behavioral health facility in Eagle this spring.

Dubbed the Precourt Healing Center, the complex will have the capacity to see up to 28 patients at once, filling a critical need in the region for adults and youth dealing with acute psychiatric crises.

While Medicaid “makes up a good bit of what keeps the lights on,” accounting for around 6% to 7% of Vail Health’s budget, Brown said the nonprofit maintains a diverse revenue stream.

That includes billing through commercial insurance and Medicare as well as grants and community donations.

The new behavioral health center, for example, was made possible in part through a major fundraising effort that kicked off in 2019 with a $15 million donation from local philanthropists.

“Losing funding is always a challenge and it’s a risk that’s always out there,” Brown said. “(But) we’re in a strong financial position, and we keep getting better. We’ve got so much support from our community.”

Vail Health isn’t a federally qualified center, but it does support Mountain Family by providing free space for its Avon and Gypsum clinics and partnering on some services — efforts which are vital to expanding access to care in mountain towns, Brown said.

The risk of Medicaid cuts, particularly for community clinics more reliant on the program, could “further destabilize the fabric of health care across the Western Slope,” Brown said.

‘Difficult to even think about’

At the state Capitol, lawmakers are soon expected to unveil their budget proposal after months of deliberation by the powerful Joint Budget Committee.

In an email, committee vice chair Rep. Shannon Bird, D-Westminster, said the committee is looking at several options for reducing Medicaid spending.

“One example is freezing the reimbursement rates we pay to health care providers for their services and reducing some rates that are higher than what the federal government pays under Medicare,” Bird said. “We would do everything in our power to protect those most vulnerable, but the brunt of these federal cuts would reduce access to vital health care.”

McCluskie, the House Speaker, said the state’s budget woes will likely persist beyond this legislative session.

State Republicans see the issue as a crisis of its own making, blaming lawmakers for funding programs with one-time pandemic-era relief funds that have now expired, leading to overspending.

McCluskie, however, has pointed to the artificial revenue and spending caps placed on the state as the root cause.

Under the 1992 voter-approved Taxpayer Bill of Rights, the state is limited, based on population growth and the rate of inflation, in how much money it can bring in. McCluskie said it’s an imperfect model that kneecaps the state’s ability to respond to changing needs, like Medicaid.

“When you’ve got an older, grayer Colorado, their need for services from the state is greater,” McCluskie said. “Right now, Colorado is projecting inflation rates lower than 3%. That’s great, except that health care costs aren’t below 3% — those have risen dramatically these last few years.”

With Medicaid’s future uncertain, rural providers are beginning to consider contingency plans. That could include leaning into more community funding in the form of grants, fundraising or local tax funds.

“Where it gets challenging is that fundraising and grants are not a long-term strategy or solution,” said Einfeld, the Northwest Colorado Health CEO. “At some point, you need to bring in different partnerships or different programs or different revenue streams in order to build that long-term sustainability.”

Moyer, with Mountain Health, said the clinic may need to look at ways to preserve cash in the short term, such as by revisiting hiring freezes.

“I am optimistic that we will find a way to continue serving our community regardless of whatever happens,” Moyer said. “But it is difficult to even think about where we could make up for that loss in revenue from potential Medicaid cuts.”

Published on SummitDaily.com.